Authored by Neeka Safdari, MSW, CSWA

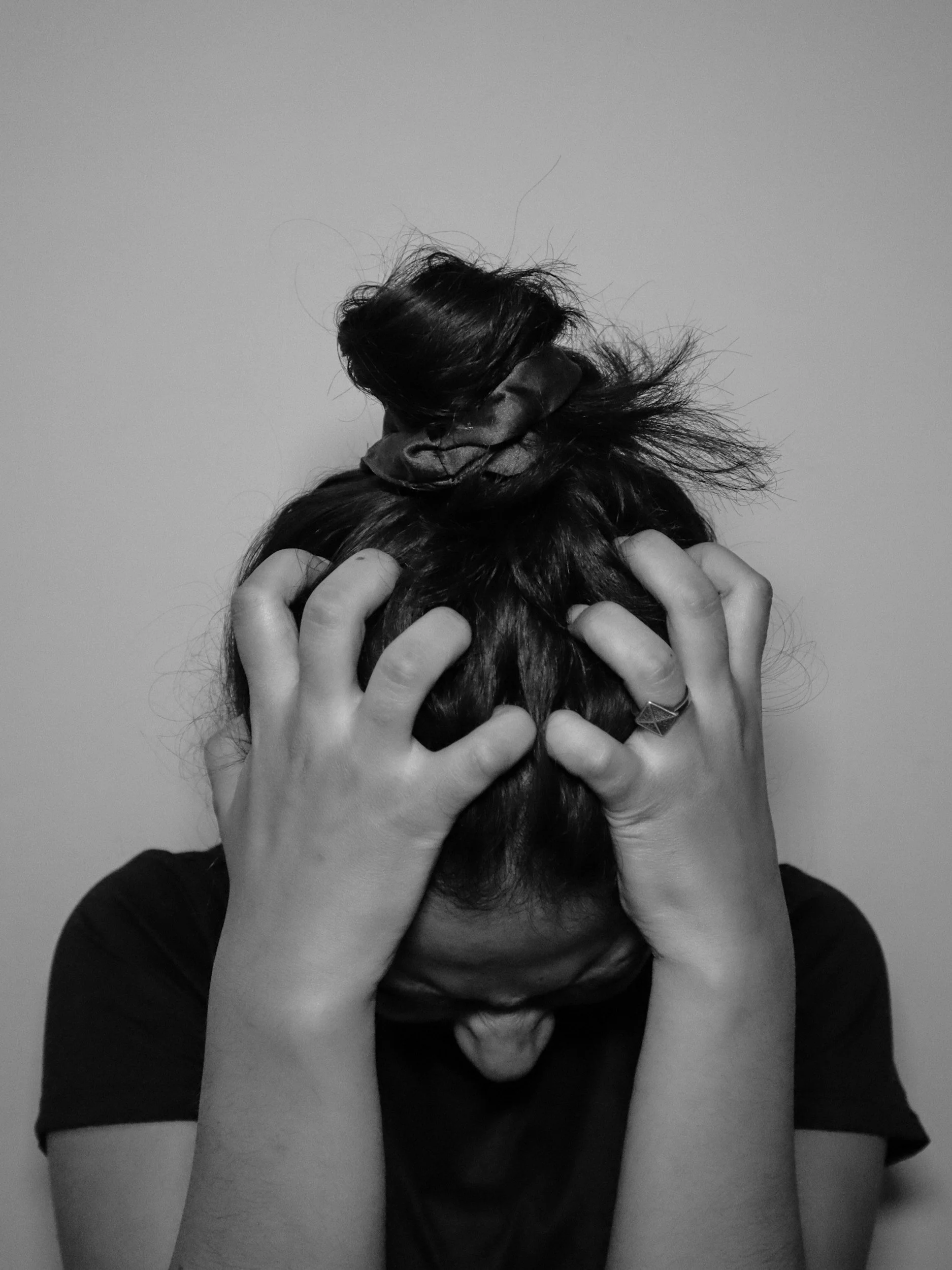

People-pleasing and perfectionism are two of many commonly talked-about topics in therapy, and, for some, coming from families of color and multicultural families can complicate the process of addressing and healing from these tendencies. Let’s talk about some of the unique contextual factors underlying people-pleasing and perfectionism within families of color.

The Need for Exceptionalism and Excellence

One common reason why folks of color learn from our parents and elders to people-please is that people in positions of power—for example, teachers, employers, members of law enforcement, etc.—expect a higher level of excellence from us, compared to our white counterparts, for the same level of respect and reward in return. Our elders have learned in schools, workplaces, and other institutional and social settings that they are always required to give their absolute best in order to do well enough to get by, and sometimes even their best is not good enough (i.e. to get an “A,” to get into a university, to get a job or promotion, to buy a home, etc.). That messaging is then, overtly or unconsciously, passed on from one generation to the next, and we internalize that we are not “good enough” unless we are super-humanly perfect and that in order to survive we need to ingratiate ourselves to people in positions of authority.

To read more about exceptionalism, see this article. (Note: This essay mentions anti-Black police violence.)

The Us-Against-the-World Mentality

Another factor often driving people-pleasing within families of color is the mentality that, under structural racism and oppression, people of color can rely only on our families, which sometimes creates room for folks to over-identify with and guilt-trip other family members—especially children. Think of the saying: “Blood is thicker than water.” Although creating a close-knit and insular family can absolutely be adaptive and protective against societal forces outside of our control, it is not uncommon for folks—again, especially children and young adults—to feel obliged or indebted to parents and other family members because of our us-against-the-world mentality. One might, for example, fail to create necessary boundaries between oneself and others in the family and/or to develop a sense of self that is partly individual, rather than entirely enmeshed with everyone else. One might also feel pressured to say “yes” to requests or demands, or feel like “no” is not an option.

To learn more about difficulty setting boundaries, see this article.

Collectivist Culture

In addition, many non-dominant, non-white cultures are collectivistic, rather than individualistic, meaning that they prioritize unity, togetherness, and the well-being of the greater group over that of any single individual. There are many benefits to this way of thinking, such as feeling a greater sense of belonging and connectedness and feeling comfortable relying on others for support. At the same time, when taken to the extreme, collectivism may erode thinking of one’s individual needs and may create a tug-of-war between prioritizing one’s own desires and needs and prioritizing those of the family and community as a whole. In these cases, it is possible that people-pleasing and meeting the needs of others may lead to exhaustion, burnout, and other adverse effects on one’s own well-being.

To further explore collectivism, individualism, and balancing the two, check out this essay.